In 2016 I started a review of Gee Vaucher’s Introspective exhibition by saying: “…[as] a teenage punk in the early 1980s it would have seemed inconceivable that Gee Vaucher’s artwork might ever grace the walls of a gallery…”. In 2023, the same thought crosses my mind about what ‘teenage me’ would have made of Vaucher’s life and work being the subject of an academic text.

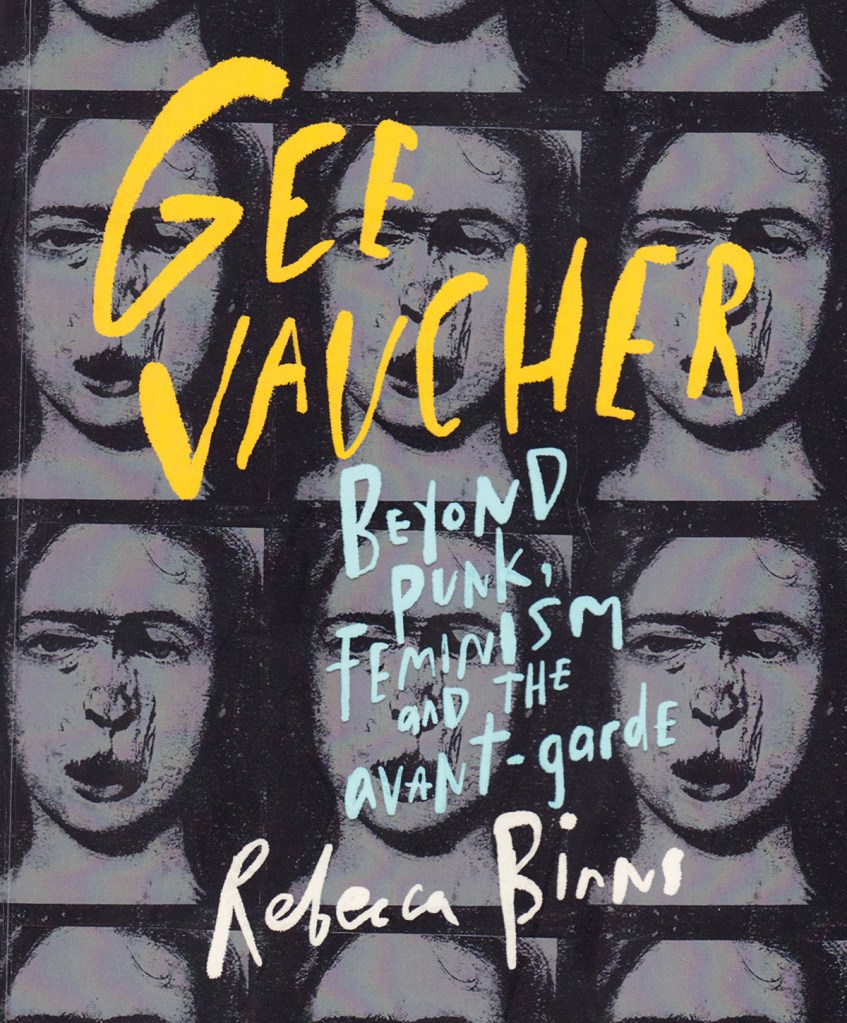

As I concluded then, 2016 was the perfect time for a retrospective exhibition, given that Donald Trump’s election victory was announced 10 days before Introspective’s private view, and with Vaucher’s artwork of the Statue of Liberty with her head in her hands appearing on the front cover of the Daily Mirror. So too now, given the current state of world affairs, is the perfect time for an intelligent recontextualization of her life’s work. As such, Rebecca Binns’ biography, Gee Vaucher: Beyond Punk, Feminism and the Avant-Garde, (2022, Manchester University Press), does just that.

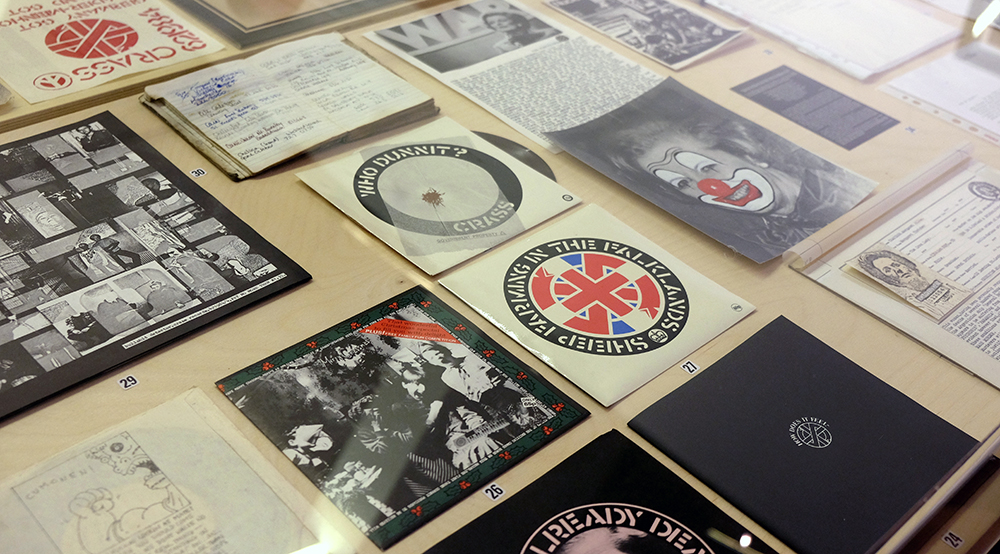

The book charts Vaucher’s working-class upbringing, her art school days, and her first forays into the art world in the early 1970s, with the avant-garde performance group EXIT and her, (now life-long), collaborator, Penny Rimbaud. After setting up the infamous communal Dial House in Essex with Rimbaud, she moved to New York to work as a commercial illustrator, using her earnings to self-publish the radical underground newspaper International Anthem. In the late 1970s she returned to the UK and back to Dial House to take charge of the visual output for Crass, the anarcho-punk band Rimbaud had set up with Steve Ignorant.

Crass, a hybrid musical / activist collective who took the first-generation punk ethos of ‘do-it-yourself’ to its logical conclusion, are for many where the story of Vaucher’s artwork might seem to both start and finish. Binns, however, as the title of her book suggests, takes us well beyond such framing, and explores the artist’s personal work that emanated on the back of Crass’ demise, the collaborations she has worked on since, her friendship with Banksy, what she is producing in the current day, before finally considering her legacy. The book perfectly complements the re-evaluation started by Introspective, highlighting the importance of Vaucher, not just as an artist and designer, but also of her influence beyond the confines of visual culture.

What is impressive in Binns’ telling of Vaucher’s story is how she has woven in so many contextual touchpoints, creating an interconnected history that crosses politics, philosophy, youth culture, art history, aesthetics, socioeconomics, protest movements, and so much more. For whatever reason someone may pick up this book, they cannot help but takeaway so much more through reading it.

It is this interconnected nature that makes for an engrossing read, and manages to site Vaucher in a much bigger social and historical continuum than her Crass days may pigeonhole her in. To illustrate this, the book covers, in turn: nineteenth-century anarchist theorist Mikhail Bakunin; the class divide; pop art; situationism; relational aesthetics; feminist theory; commercial illustration; the underground press; counter-culture; the aesthetics of collage and drawing; arts education; graphic design; the direct action movement of the 1980s; the New Left of the 1990s; pornography; Young British Artists, (YBA); the ‘art market’; Palestine; the Occupy movement; Extinction Rebellion; and then some. While this may seem exhausting as a list, the author does deft work of structuring and relating these topics to each other through Vaucher’s life and work. In drawing a sightline through all of these contexts, Gee Vaucher is repositioned as an important figure in art, design, and social history. As someone who can remember the derision that surrounded Crass in the music press of the 1980s, and who has been aghast at the lack of attention given to Vaucher in art history, (especially in graphic design titles supposedly dedicated to the visual art of agit-prop and protest), Gee Vaucher: Beyond Punk, Feminism and the Avant-Garde goes a long way to addressing this.

In terms of her artistry, the time spent at art school and dedication to craft ensures her skill is evident in all that she does. This is explored in depth throughout the book as much as politics are. Whilst many anarcho-punk graphics of the 1980s were poorly executed in regard to skill level, sometimes deliberately so as a political semiotic choice, Vaucher’s artwork is expertly drawn and photorealistic in nature. Much of her work looks like collage, even though it is actually hand-drawn. The political artist Peter Kennard comments that when he was Head of Photography at the Royal College of Art, (RCA), he would present students with Vaucher’s work as “fine examples of photomontage”, (p67), only to realise several years later after seeing some of her original artwork that they were in fact drawings.

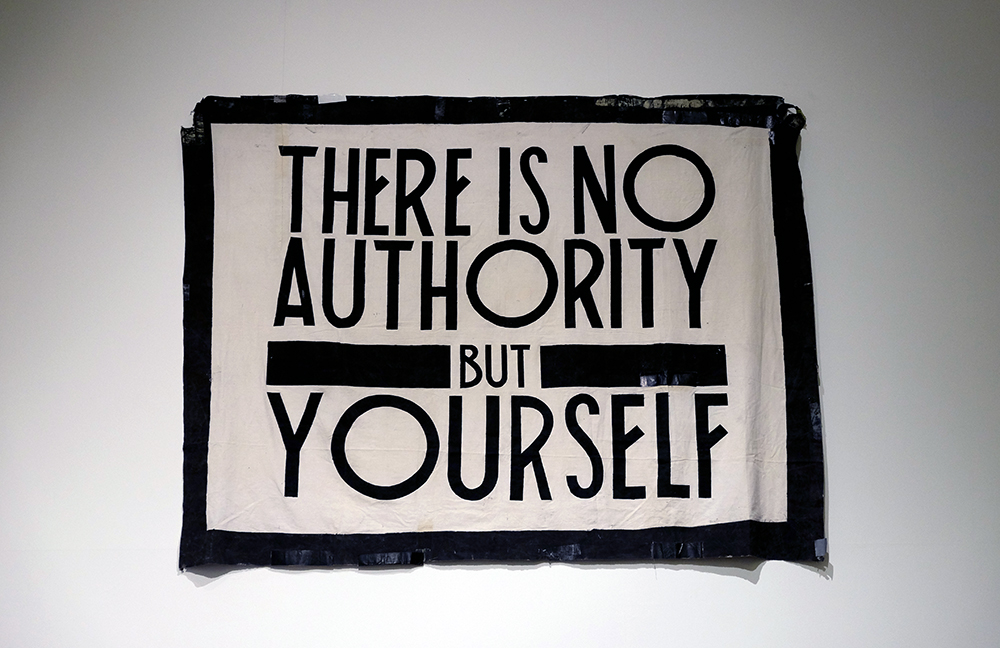

More personally, Gee Vaucher: Beyond Punk, Feminism and the Avant-Garde manages to capture a sense of Vaucher as a person, in an honest and often personal account of her life, drawn from extensive interviews and research by the author. It reveals her as a strong yet modest woman in a patriarchal society, able to navigate and influence the direction of her life on her own terms. She has both taken and rejected opportunities as they arise, helped by her lack of ego or interest in elevating her status as an artist, which has allowed her to not follow career objectives, and instead, underpin the decisions she makes based on her own personal set of ethics. While she instinctively rejects ‘ists’ and ‘isms’ and being boxed into categories, many of her beliefs can clearly be rationalised within terms such as anarchism and feminism, and she has reluctantly come to accept some of these descriptors as necessary due to her audience’s insistence of using such terminology. But even in this, it is abundantly clear how much of her world view chimes with those of Crass lyrics and philosophical stance. The phrase often used by the band: “There is no authority but yourself”, is central to her very being.

That said, Vaucher’s views occasionally appear to lack empathy and be out of step with someone who, in most respects, understands how power structures create victims. One such occasion, when talking about flashing, she says: “I’ve been flashed at, touched up, but nothing I couldn’t handle … I’m not saying it’s right, but you would have to find your own way of dealing with it…”. She goes on to say: “What must be the damage caused? I can only imagine it. I can’t say that I could ever fully understand the depth of such an experience. I could only observe that for each woman it was different. Some women come to terms with it in a positive way. Some women, you kind of knew, were going to use it as a crutch for the rest of her life and that made me sad and I thought; I don’t know how to help”. (p65)

Reading this while the sentencing for flashing of the rapist-murderer-policeman Wayne Couzens was in the news, made the comment seem naïve and at odds to Vaucher’s otherwise strongly held feminist beliefs. Elsewhere, the criticism that Crass’ idea of anarchy and rejection of societal systems could be seen as sitting close to conservative libertarianism is objectively documented by Binns, a view quickly shot-down by Rimbaud in stating that Crass believed in collectivism rather than individualism. But Vaucher’s leaning towards survival of the (mentally) fittest, demonstrates a detachment to the sense of ‘sisterhood’ which I wasn’t expecting to read. It does go to show her as a free thinker though, and not someone who buys hook, line and sinker into a philosophical or ‘accepted’ position on anything. Vaucher has no ‘one world’ view, even if she heavily leans in certain directions. And while much of her work might aesthetically be black and white, the contexts explored within it can often be much more nuanced, allowing the reader in, in order to be able to interpret the work for themselves.

This revealing of Vaucher’s personality in Binns’ biography may partly explain Rimbaud’s comment that: “I have known Gee Vaucher for over fifty years, but perhaps I could better define our relationship by stating that I have not known her for over fifty years”, (p167).

The time is right for Gee Vaucher to be recontextualised, as her life’s work is much greater than the sum of its parts. Introspective proved this visually, as now does Gee Vaucher: Beyond Punk, Feminism and the Avant-Garde. Beyond this though, Rebecca Binns’ biography is an important contribution to a large canon of texts about agit-prop, music graphics, feminism and protest movements. It should become a go-to read for anyone interested in any of the above, tying in as it does so many contexts and resituating Vaucher as a key figure at the centre of many of them, despite the fact that much of the time she has been working from the side lines.

You must be logged in to post a comment.